The end of specialisations? How AI is reshaping what it means to build digital products

I remember when I first started hearing about programming. There was this almost mythical figure called "the programmer" — someone who mastered the company's language and solved anything that involved a computer. But here's something most people don't know: before that, the word "computer" didn't even refer to a machine. It was a job title.

How we got here

Back in the day, "computer" was the job title for people who did super complex mathematical calculations by hand. They worked with tables, slide rules, and... a lot of patience.

Human computers at work in a mid-20th century office, performing complex calculations by hand.

Human computers at work in a mid-20th century office, performing complex calculations by hand.

When the first computers came along (now we're talking about the electronic kind we know today), these people were the first to "program" them — because they already understood the logic behind all those calculations.

Fun fact: Margaret Hamilton was the one who coined the term "software engineer" to describe her work — which was basically building the software that landed humans on the moon.

The point here isn't just historical. It's that our industry has never been static. From the very beginning, it adapts to whatever technology allows. And sometimes that adaptation changes everything: what we build, how we build it, and how we structure teams to deliver.

In the 90s and early 2000s, the tech market worked differently. If you looked at job listings, you'd see things like "ASP.NET Developer," "Java Programmer," "PHP Analyst," "Delphi Developer." The language was the professional's identity. And it made total sense: frameworks were heavy, libraries were different, and switching stacks meant basically starting from scratch.

And it wasn't just the code. It was the whole ecosystem. The way you thought about architecture, build tools, deployment models, IDEs — everything was specific to that language. Moving from Java to Ruby was almost like changing careers.

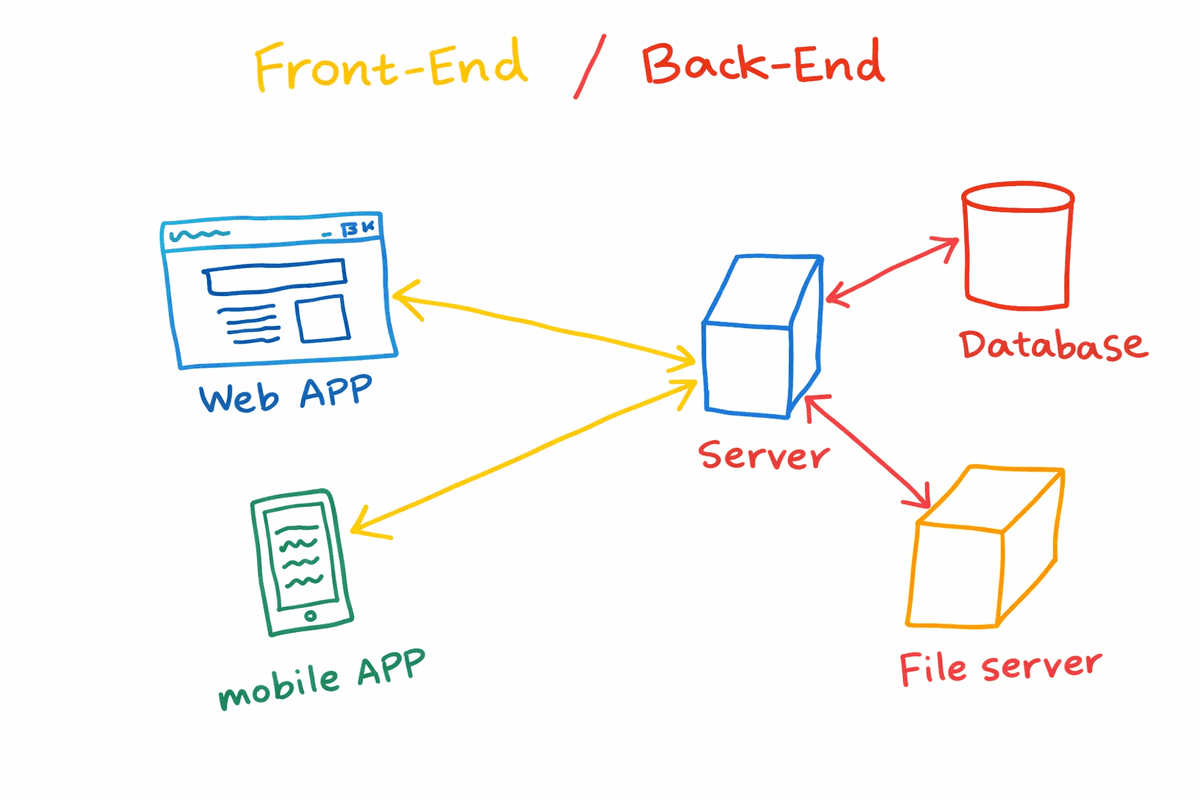

Around the mid-2010s, things started to shift. Job postings began asking for "backend developer" or "frontend developer" instead of a specific language. The specialisation axis was changing.

Why? A lot of things happening at once: the JavaScript boom on the frontend with frameworks like Angular and React. The backend fragmented across several modern languages (Go, Node, Rust, Kotlin). And companies realised that a good backend dev who knew Java could learn Go in a few weeks — what mattered was understanding API concepts, databases, concurrency, not the specific syntax.

The shift from language-defined roles to discipline-based specializations like frontend and backend development.

The shift from language-defined roles to discipline-based specializations like frontend and backend development.

Frontend became its own world. State management, build systems, componentization, automated testing, accessibility. Meanwhile, mobile held its ground with iOS and Android as completely different ecosystems — years of platform-specific knowledge that didn't transfer easily.

What AI actually changes

And then we hit 2024, 2025. Things got interesting.

Dario Amodei, Anthropic's CEO, mentioned in a recent interview that the vast majority of code at the company is now AI-generated. Even accounting for some exaggeration or context-specific nuance, the direction is clear — and we're seeing similar patterns in our own work and across the teams we collaborate with.

A backend dev who's never touched React can, with AI assistance, create a functional interface in hours. A frontend dev who knows nothing about Kubernetes can configure a basic deployment following assisted suggestions. A web engineer can prototype a mobile app in Flutter without ever having studied Dart.

This doesn't mean the generated code is perfect. It's not. But it's good enough to unblock the work. And in many contexts — especially startups, MVPs, internal tools — good enough is exactly what you need to validate an idea before investing heavily. The threshold shifts depending on what you're building: a prototype for investor validation has different quality requirements than a medical device interface. And there's an accumulation effect worth watching — stack enough "good enough" solutions and you might find yourself with a system no one fully understands.

But "good enough" has limits. Take mobile. An experienced iOS engineer has years of nuanced understanding about what makes a good iOS app — not just one that works. Swipe transitions versus stacking for navigation. How the app responds to Android's hardware back button. The micro-interactions that feel native versus the ones that feel off. And it's not just UI polish. AI might generate a list view that works fine with 50 items but falls apart with 5,000. It can add ARIA labels, but it doesn't know how screen reader users actually navigate. It won't think to implement "no surprise shipping costs" in a checkout flow — that kind of decision comes from years of watching conversion data. These are craft touches, and AI doesn't naturally surface them. A web dev wielding Claude won't even know to ask. The code might be functionally correct, but something's missing — and you won't notice until you hand it to someone who lives in that world.

There's another limitation worth naming. AI is, by nature, backward-facing. It's trained on the sum of what's been written before — which means it reflects the average of past solutions. When you're working with established patterns, that's a strength. But when you're genuinely exploring new territory, pushing into approaches that don't have much precedent? AI gets less useful. It's not its area of specialty. And if everyone uses AI to generate similar patterns, we risk a kind of convergence toward mediocrity — who's pushing the boundaries that become tomorrow's training data? In emerging fields like spatial computing or AR interfaces, the training data is thin. We've had projects where AI suggestions kept pushing us toward patterns that experienced engineers recognised as outdated — they'd lived through why those patterns got replaced. AI doesn't have that institutional memory.

The balance between AI-generated code and human craft — speed versus nuanced understanding.

The balance between AI-generated code and human craft — speed versus nuanced understanding.

Here's where it gets nuanced, though. Even deep review of AI-generated code is being questioned in some teams. The argument: if the AI generates code that works, passes the tests, and solves the problem, is it worth having someone spend hours reviewing every line?

This isn't without risk. Code without review accumulates technical debt, might have security gaps — subtle vulnerabilities that pass tests but fail under adversarial conditions — and can become a maintenance burden fast. We've seen this pattern play out — and it's exactly why having experienced engineers in the loop matters more than ever. Not to review every line, but to make the architectural calls and spot the patterns that compound over time. That said, in small teams under delivery pressure, the practical reality is that exhaustive line-by-line review often doesn't happen. And in many cases, if the code works, passes tests, and solves the problem — teams move on.

This ties into an uncomfortable question I've seen floating around in nerd corners of the internet: if AI is going to rewrite the code anyway, does code quality even matter? The argument goes something like this — stop obsessing over clean architecture and pristine abstractions, because no human is going to maintain this code. The next iteration will just be another prompt that regenerates everything from scratch. On one hand, there's something almost liberating about that framing. It shifts the focus from code-as-artifact to code-as-disposable-output. Speed and iteration over long-term maintainability. On the other hand, this assumes a greenfield rewrite every sprint, and that's not how most products evolve. You're usually modifying existing systems, debugging production issues, maintaining backward compatibility. Dependencies and integrations create constraints. Code rarely gets thrown away as cleanly as this argument suggests. What happens when the AI doesn't rewrite everything? What about the parts that stick around, accumulating complexity while no one truly understands them? And what about tests? If AI generates the code and the tests, who validates the validator? I don't have a clean answer. It's a genuine tension — and the ultimate evaluation might be simpler than we think: are users voting with their attention or not?

Where the real value lives now

I don't think software engineers will be replaced. But the work is shifting — it's already shifting. If AI can write code, what's left that's uniquely human?

Understanding the actual problem. AI generates code for whatever you ask. But asking the right thing — understanding what the business needs, what users actually want, what the real constraints are — that's still deeply human.

Architecture decisions. Which database to use? How to split the services? Where to put the complexity? These decisions have long-term consequences that require experience and judgment. AI can suggest options, but someone needs to choose and own the outcome.

Critical review at the system level. Even if line-by-line review decreases, someone needs to understand if the solution makes sense in the bigger picture. Whether the approach will create performance problems at scale. Whether it's sustainable for the team that'll maintain it.

Communication and alignment. Translating vague requirements into clear specs. Negotiating scope. Explaining trade-offs to stakeholders who aren't technical. That's not going to AI anytime soon — and honestly, it's where a lot of projects succeed or fail.

There's also a question we haven't fully answered: if AI handles more of the implementation, how do junior engineers develop the systems thinking that makes senior engineers valuable? That knowledge transfer problem isn't going away.

The profile that's emerging

If I had to describe what we're optimising for in our teams now, it would be something like this: people who deeply understand systems (not just a language), who know how to use AI as a leverage tool, who can navigate any part of the stack when needed, but who still have areas where they go deeper.

To be fair, the best senior engineers have always thought this way. Great backend developers always understood frontend constraints. Strong mobile developers always understood API design. What's changed isn't the ideal profile — it's that AI closes the execution gap for people who already think this way. The need for systems thinkers isn't new. What's new is how much they can get done.

It's almost a return to the generalist, but different. Not someone who knows a little bit of everything superficially. It's someone with real depth in one area who uses modern tools to have reach across the whole product.

For the companies we work with, this shift is significant. Instead of needing separate specialists for every layer of the stack, a smaller, senior team that knows how to leverage AI effectively can move faster and with more coherence. The coordination overhead drops. The context stays intact. The product feels like one thing, not three systems stitched together.

We've been investing heavily in how our teams use AI — though it's worth being honest: adoption isn't uniform. Some engineers have fully shifted to prompt-driven workflows, barely touching code directly. Others use AI more as an accelerator for boilerplate while still relying on their normal practices for the core work. Both are valid. The tool is powerful, but how much you lean into it still varies by person, by project, by what you're building.

What this means if you're building something

If you're a founder trying to get to market, or a CTO thinking about how to structure your next product team, or an engineering manager trying to modernize how your team works — the calculus has changed.

The question isn't "do we need a frontend dev, a backend dev, and a mobile dev?" anymore. It's "do we have people who can think through the whole problem and use the right tools to solve it?"

And if you're evaluating partners to build with, the question isn't just "do they know React or Node or whatever." It's "do they know how to use AI to move fast without creating a mess they can't maintain?"

One tension we're still working through: this model seems to work best with a single person driving the technical direction — someone who holds the vision and uses AI to execute fast. Add a second or third collaborator, and coordination complexity creeps back in. Whose prompts win? Who owns the architectural decisions when the AI is doing the heavy lifting? For early-stage and prototyping work, the single-driver model fits well. But let's be honest: we know what happens when everything depends on one person. They leave, the knowledge leaves with them. The prompts are in their head. The context is in their head. The fact that AI-augmented development currently works best with a single driver isn't a feature — it's a limitation of the tooling we haven't solved yet. We need better patterns here. Shared prompt libraries, maybe. Architectural decision records. Ways to distribute context beyond one person's head. That's still unsolved.

Worth naming what bad looks like, too. Teams where no one can explain what the AI-generated code actually does. Where prompts become tribal knowledge held by one person. Where "it works" is the only quality bar because no one wants to touch something they didn't write and can't fully read. Where debugging means regenerating from scratch because understanding the existing code feels impossible. These are warning signs — and they're easier to spot than to fix once you're deep in.

That's the bet we've made. The tools will keep changing — they always have. What doesn't change is the need to deeply understand what you're building and why. The AI handles more of the how. The judgment about what and why? That's where the work is now.